Padre Pio/es: Difference between revisions

PeterDuffy (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

(Updating to match new version of source page) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Prestó servicio en el cuerpo médico durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero era demasiado enfermizo para poder continuar. En 1918 fue transferido al pequeño convento del siglo <small>XVI</small> de Nuestra Señora de Gracia, a unas a doscientas millas al este de Roma. Desde entonces jamás abandonó esa aislada zona montañosa. Sin embargo, antes de fallecer, en 1968, recibía cinco mil cartas al mes y miles de visitantes. Se había hecho popular por su piedad y sus milagros. | Prestó servicio en el cuerpo médico durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero era demasiado enfermizo para poder continuar. En 1918 fue transferido al pequeño convento del siglo <small>XVI</small> de Nuestra Señora de Gracia, a unas a doscientas millas al este de Roma. Desde entonces jamás abandonó esa aislada zona montañosa. Sin embargo, antes de fallecer, en 1968, recibía cinco mil cartas al mes y miles de visitantes. Se había hecho popular por su piedad y sus milagros. | ||

El Padre Pío está considerado como el primer sacerdote católico en llevar las heridas de Cristo. ([[Special:MyLanguage/Saint Francis|San Francisco]] fue la primera ''persona'' en recibir los estigmas). También tenía los dones de la clarividencia, la conversión, el discernimiento de espíritus, las visiones, la bilocación, la curación y la profecía. Se dice que una vez, cuando un sacerdote polaco recién ordenado fue a verlo, el Padre Pío comentó: «Algún día serás papa». Tal como lo profetizó, ese sacerdote se convirtió en el papa Juan Pablo II. | El Padre Pío está considerado como el primer sacerdote católico en llevar las heridas de Cristo. ([[Special:MyLanguage/Saint Francis|San Francisco]] fue la primera ''persona'' en recibir los estigmas). También tenía los dones de la clarividencia, la conversión, el discernimiento de espíritus, las visiones, la bilocación, la curación y la profecía. Se dice que una vez, cuando un sacerdote polaco recién ordenado fue a verlo, el Padre Pío comentó: «Algún día serás papa». Tal como lo profetizó, ese sacerdote se convirtió en el papa Juan Pablo II.<ref>Kenneth L. Woodward, ''Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn’t, and Why'' (Haciendo santos: cómo determina la Iglesia Católica quién se convierte en santo, quién no lo hace y por qué), (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 157; C. Bernard Ruffin, ''Padre Pio: The True Story'' (Our Sunday Visitor, 1982), p. 361.</ref> | ||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Author Kenneth L. Woodward writes in his book ''Making Saints'': | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

<blockquote>From early adolescence on, Padre Pio spoke frequently in visions with [[Jesus]], [[Mother Mary|Mary]] and his own [[guardian angel]]. Those were the good times. Many a night, he reported, was spent in titanic struggles with the Devil, which left him bloodied, bruised and exhausted in the morning.<ref>Woodward, ''Making Saints'', pp. 156–57.</ref></blockquote> | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Author Michael Grosso speaks further of these struggles. He says: | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

These encounters were physical. In one monastery where he served, you can still see claw marks and splattered ink spots made by the alleged demons. Once, the iron bars of the monk’s cell were found twisted out of shape after a night of grappling with invisible forces. Although no one beside the Padre ever saw the demons, the din they made was often heard by eavesdropping monks. Even more striking, Padre Pio was often found unconscious, sometimes on the floor beside his bed, covered with bruises from the uncanny assaults. On another occasion he was found with broken bones in his arms and legs. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

The point I want to make about “demons” and evolution is this: It does appear, as a matter of psychological fact, that the more one advances in higher states of consciousness, the greater the likelihood of attracting combative, destructive forces that try to drag you back down to ordinary reality. The story of the [[Buddha]] struggling to meditate on the Immovable Spot under the Bo tree is a classic Eastern illustration. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

In Pio’s case, the combat occurred at two levels: Throughout his life he was molested by invisible, “diabolic” forces. But throughout his life he was also persecuted by jealous, envious and malicious human beings, often individuals within the Church hierarchy.<ref>Michael Grosso, ''Who Is Padre Pio'', pp. 3–4.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

For ten years he was not permitted to celebrate Mass publicly or hear confessions. | |||

</div> | |||

[[File:PadrePiowithChristChild.jpg|thumb|<span lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr">Padre Pio with the Christ Child</span>]] | |||

<span id="His_service_as_a_confessor"></span> | <span id="His_service_as_a_confessor"></span> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 54: | ||

Al Padre Pío se le reconoce el don de «leer los corazones»; es decir, la capacidad de ver lo que hay en el alma de los demás y conocer sus pecados sin oír una sola palabra del penitente. A medida que creció su reputación, también lo hicieron las filas hacia su confesionario, hasta el punto de que por algún tiempo sus compañeros capuchinos expedían boletos por el privilegio de confesarse con el Padre Pío. Algunas veces, cuando un pecador no podía acudir a él, el Padre Pío acudía al pecador, se cuenta, aunque no de la manera normal. | Al Padre Pío se le reconoce el don de «leer los corazones»; es decir, la capacidad de ver lo que hay en el alma de los demás y conocer sus pecados sin oír una sola palabra del penitente. A medida que creció su reputación, también lo hicieron las filas hacia su confesionario, hasta el punto de que por algún tiempo sus compañeros capuchinos expedían boletos por el privilegio de confesarse con el Padre Pío. Algunas veces, cuando un pecador no podía acudir a él, el Padre Pío acudía al pecador, se cuenta, aunque no de la manera normal. | ||

Sin salir de su habitación, el fraile aparecía hasta en Roma para escuchar una confesión o consolar a los enfermos. Es decir, estaba dotado del poder de «bilocación», o la capacidad de estar presente en dos sitios al mismo tiempo<ref> | Sin salir de su habitación, el fraile aparecía hasta en Roma para escuchar una confesión o consolar a los enfermos. Es decir, estaba dotado del poder de «bilocación», o la capacidad de estar presente en dos sitios al mismo tiempo<ref>Woodward, ''Making Saints'', págs. 156-57.</ref>. | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Padre Pio had the ability to help souls walk the razor's edge. Like a guru in the Eastern tradition, he was able to wake up people to their true state of ignorance and turn souls back to God. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Father Alberto D’Apolito tells this story of a blind man who was converted by what he called Padre Pio’s “loving rudeness.” A priest from the region of Salento told Father Alberto: | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

“Father Alberto, there will come to you a blind man of my parish, who had gone to San Giovanni Rotondo for confession. But Padre Pio, upon seeing him, without allowing him to come close, shouted: ‘You filthy person, go away!’ I think that Padre Pio was too harsh with him.” | |||

</blockquote> | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Father Alberto said: | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

“I cannot say anything, for I do not know the reason for such severity. He certainly must have had his reasons. When I meet this blind person, I will question him.” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

In fact, one morning after Mass, a few days after my arrival in that town, a blind man accompanied by a little girl came to me and said: “Do you know Padre Pio well?” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

At my affirmative reply, he added: “Would you say he is a saint?” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

“No,” I replied. “In order to be a saint, he must first die, and then, after a rigorous process, he must be canonized by the Church." | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Then the man said: “Father Alberto, I went to San Giovanni Rotondo to go to confession. I was about to approach the confessional when Padre Pio, seeing me, shouted: ‘You filthy person, go away!’ Offended and angry, I went away swearing. If he were a saint, he would not receive sinners in this manner.” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

I replied: “Yes, Padre Pio has been very harsh. He used a strong manner with you. He may have had a reason that is unknown to us.” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Meanwhile, I already suspected the reason for which Padre Pio had called him a filthy person and sent him away. But I wanted to be sure, through the words of the blind man himself. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

As Father Alberto questioned the man, he found out that he was sleeping with the young woman who was assisting him but refused to marry her. When the man revealed this fact Father Alberto said: | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

“Now I can tell you that Padre Pio is a saint, a chosen one of God. He sent you away, calling you a filthy person, without knowing you, because he smelled from a distance the stench of your sins; because the Lord made him see the abyss in which your soul has fallen and the mud that covers it and disfigures it. You went to San Giovanni Rotondo with the hope of gaining the grace of the sight of the body, and not of the soul. This is the reason why Padre Pio called you a ‘filthy person,’ and sent you away—to make you reflect, to shake you and convert you.” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Not convinced by my words, the blind man got up and went away. [But] after a few days he returned, and approaching the confessional where I was, he said to me: “Father, I need to speak with you.” | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Without making him wait, I left the confessional and went with him behind the main altar. Sitting down, he said to me: “Father, I have meditated for a long time on your words. Yes, what you told me last time was true. I had gone to Padre Pio with the hope of receiving the miracle of my sight, and not to change my life. Padre Pio was right in calling me a filthy person, for I have always been one. I, too, am convinced that Padre Pio is a saint. The young woman who assists me and I have decided to get married as soon as possible. Now, I beg of you to hear the confession of my sins, and to reconcile me with God. As soon as our situation is rectified, we will go to San Giovanni Rotondo to thank Padre Pio for this great grace obtained from God, with his prayers and his loving rudeness.”<ref>Alberto D’Apolito, ''Padre Pio of Pietrelcina'', pp. 253–56.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

</div> | |||

Uno de sus devotos escribió: | |||

<blockquote>Si algunas veces es severo es porque muchas personas se acercan al confesionario con ligereza, sin dar al sacramento la verdadera importancia que tiene<ref>Laura Chandler White, trad., ''Who is Padre Pio? (¿Quién es el Padre Pío?)'' (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1974), pág. 41.</ref>.</blockquote> | <blockquote>Si algunas veces es severo es porque muchas personas se acercan al confesionario con ligereza, sin dar al sacramento la verdadera importancia que tiene<ref>Laura Chandler White, trad., ''Who is Padre Pio? (¿Quién es el Padre Pío?)'' (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1974), pág. 41.</ref>.</blockquote> | ||

[[File:Padre Pio during Mass.jpg|thumb|Padre Pio celebrando la Misa]] | [[File:Padre Pio during Mass.jpg|thumb|Padre Pio celebrando la Misa]] | ||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

== His celebration of the Mass == | |||

</div> | |||

Mucha gente que fue a escuchar al Padre Pío celebrar misa quedó | Mucha gente que fue a escuchar al Padre Pío celebrar misa quedó | ||

| Line 59: | Line 157: | ||

Cuando le contó a su madre la historia de cómo había escapado, ella dijo: «Ese era el Padre Pío. Le recé tanto por ti». Entonces le enseñó una imagen del Padre. «¡Es él!», dijo el joven piloto. | Cuando le contó a su madre la historia de cómo había escapado, ella dijo: «Ese era el Padre Pío. Le recé tanto por ti». Entonces le enseñó una imagen del Padre. «¡Es él!», dijo el joven piloto. | ||

Después fue a agradecerle al Padre Pío su intervención. «No ha sido la única vez que te he salvado», dijo el Padre Pío. «En Monastir, cuando tu avión fue alcanzado, lo hice planear hacia tierra a salvo». El piloto se quedó asombrado porque el acontecimiento al que se refería el Padre había ocurrido algún tiempo atrás, y no había ninguna manera normal en la que pudiera saberlo<ref>Stuard Holroyd, ''Psychic Voyages (Viajes psíquicos)'' (London: Danbury Press, 1976), págs. 44–45.</ref>. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<span id="His_service_today"></span> | <span id="His_service_today"></span> | ||

| Line 72: | Line 169: | ||

{{MTR-es-vol2}}, “Padre Pío”. | {{MTR-es-vol2}}, “Padre Pío”. | ||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, December 31, 1995. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, January 3, 1993. | |||

</div> | |||

[[Category:Seres celestiales]] | [[Category:Seres celestiales]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Christian saints{{#translation:}}]] | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:38, 6 January 2026

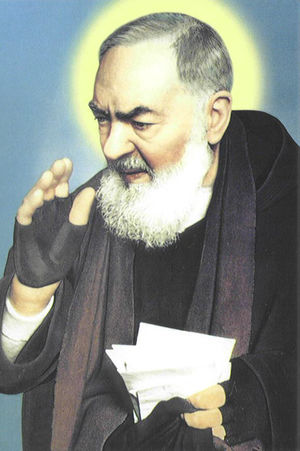

El Padre Pío fue el famoso monje italiano del siglo xx que durante cincuenta años llevó en sus manos, pies y costado las heridas del Cristo crucificado, llamadas estigmas.

Su vida

Este sacerdote amable y humilde nació el 25 de mayo de 1887, con el nombre de Francesco Forgione, en una de las zonas más pobres y atrasadas del sur de Italia. A la edad de quince años entró a un monasterio de franciscanos capuchinos, y fue ordenado al sacerdocio en 1910.

Prestó servicio en el cuerpo médico durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero era demasiado enfermizo para poder continuar. En 1918 fue transferido al pequeño convento del siglo XVI de Nuestra Señora de Gracia, a unas a doscientas millas al este de Roma. Desde entonces jamás abandonó esa aislada zona montañosa. Sin embargo, antes de fallecer, en 1968, recibía cinco mil cartas al mes y miles de visitantes. Se había hecho popular por su piedad y sus milagros.

El Padre Pío está considerado como el primer sacerdote católico en llevar las heridas de Cristo. (San Francisco fue la primera persona en recibir los estigmas). También tenía los dones de la clarividencia, la conversión, el discernimiento de espíritus, las visiones, la bilocación, la curación y la profecía. Se dice que una vez, cuando un sacerdote polaco recién ordenado fue a verlo, el Padre Pío comentó: «Algún día serás papa». Tal como lo profetizó, ese sacerdote se convirtió en el papa Juan Pablo II.[1]

Author Kenneth L. Woodward writes in his book Making Saints:

From early adolescence on, Padre Pio spoke frequently in visions with Jesus, Mary and his own guardian angel. Those were the good times. Many a night, he reported, was spent in titanic struggles with the Devil, which left him bloodied, bruised and exhausted in the morning.[2]

Author Michael Grosso speaks further of these struggles. He says:

These encounters were physical. In one monastery where he served, you can still see claw marks and splattered ink spots made by the alleged demons. Once, the iron bars of the monk’s cell were found twisted out of shape after a night of grappling with invisible forces. Although no one beside the Padre ever saw the demons, the din they made was often heard by eavesdropping monks. Even more striking, Padre Pio was often found unconscious, sometimes on the floor beside his bed, covered with bruises from the uncanny assaults. On another occasion he was found with broken bones in his arms and legs.

The point I want to make about “demons” and evolution is this: It does appear, as a matter of psychological fact, that the more one advances in higher states of consciousness, the greater the likelihood of attracting combative, destructive forces that try to drag you back down to ordinary reality. The story of the Buddha struggling to meditate on the Immovable Spot under the Bo tree is a classic Eastern illustration.

In Pio’s case, the combat occurred at two levels: Throughout his life he was molested by invisible, “diabolic” forces. But throughout his life he was also persecuted by jealous, envious and malicious human beings, often individuals within the Church hierarchy.[3]

For ten years he was not permitted to celebrate Mass publicly or hear confessions.

Su servicio como confesor

Una de las cosas por las que el Padre Pío era más conocido era su capacidad como confesor. Kenneth Woodward escribe: «La mayor parte de las energías del Padre Pío estaban dedicadas a la oración intensa, la celebración de la misa y, sobre todo, a escuchar confesiones». Gente de todo el mundo acudía en masa a su puerta para que escuchara sus confesiones. Woodward dice:

Al Padre Pío se le reconoce el don de «leer los corazones»; es decir, la capacidad de ver lo que hay en el alma de los demás y conocer sus pecados sin oír una sola palabra del penitente. A medida que creció su reputación, también lo hicieron las filas hacia su confesionario, hasta el punto de que por algún tiempo sus compañeros capuchinos expedían boletos por el privilegio de confesarse con el Padre Pío. Algunas veces, cuando un pecador no podía acudir a él, el Padre Pío acudía al pecador, se cuenta, aunque no de la manera normal.

Sin salir de su habitación, el fraile aparecía hasta en Roma para escuchar una confesión o consolar a los enfermos. Es decir, estaba dotado del poder de «bilocación», o la capacidad de estar presente en dos sitios al mismo tiempo[4].

Padre Pio had the ability to help souls walk the razor's edge. Like a guru in the Eastern tradition, he was able to wake up people to their true state of ignorance and turn souls back to God.

Father Alberto D’Apolito tells this story of a blind man who was converted by what he called Padre Pio’s “loving rudeness.” A priest from the region of Salento told Father Alberto:

“Father Alberto, there will come to you a blind man of my parish, who had gone to San Giovanni Rotondo for confession. But Padre Pio, upon seeing him, without allowing him to come close, shouted: ‘You filthy person, go away!’ I think that Padre Pio was too harsh with him.”

Father Alberto said:

“I cannot say anything, for I do not know the reason for such severity. He certainly must have had his reasons. When I meet this blind person, I will question him.”

In fact, one morning after Mass, a few days after my arrival in that town, a blind man accompanied by a little girl came to me and said: “Do you know Padre Pio well?”

At my affirmative reply, he added: “Would you say he is a saint?”

“No,” I replied. “In order to be a saint, he must first die, and then, after a rigorous process, he must be canonized by the Church."

Then the man said: “Father Alberto, I went to San Giovanni Rotondo to go to confession. I was about to approach the confessional when Padre Pio, seeing me, shouted: ‘You filthy person, go away!’ Offended and angry, I went away swearing. If he were a saint, he would not receive sinners in this manner.”

I replied: “Yes, Padre Pio has been very harsh. He used a strong manner with you. He may have had a reason that is unknown to us.”

Meanwhile, I already suspected the reason for which Padre Pio had called him a filthy person and sent him away. But I wanted to be sure, through the words of the blind man himself.

As Father Alberto questioned the man, he found out that he was sleeping with the young woman who was assisting him but refused to marry her. When the man revealed this fact Father Alberto said:

“Now I can tell you that Padre Pio is a saint, a chosen one of God. He sent you away, calling you a filthy person, without knowing you, because he smelled from a distance the stench of your sins; because the Lord made him see the abyss in which your soul has fallen and the mud that covers it and disfigures it. You went to San Giovanni Rotondo with the hope of gaining the grace of the sight of the body, and not of the soul. This is the reason why Padre Pio called you a ‘filthy person,’ and sent you away—to make you reflect, to shake you and convert you.”

Not convinced by my words, the blind man got up and went away. [But] after a few days he returned, and approaching the confessional where I was, he said to me: “Father, I need to speak with you.”

Without making him wait, I left the confessional and went with him behind the main altar. Sitting down, he said to me: “Father, I have meditated for a long time on your words. Yes, what you told me last time was true. I had gone to Padre Pio with the hope of receiving the miracle of my sight, and not to change my life. Padre Pio was right in calling me a filthy person, for I have always been one. I, too, am convinced that Padre Pio is a saint. The young woman who assists me and I have decided to get married as soon as possible. Now, I beg of you to hear the confession of my sins, and to reconcile me with God. As soon as our situation is rectified, we will go to San Giovanni Rotondo to thank Padre Pio for this great grace obtained from God, with his prayers and his loving rudeness.”[5]

Uno de sus devotos escribió:

Si algunas veces es severo es porque muchas personas se acercan al confesionario con ligereza, sin dar al sacramento la verdadera importancia que tiene[6].

His celebration of the Mass

Mucha gente que fue a escuchar al Padre Pío celebrar misa quedó transformada. El mismo devoto escribe:

Cuando la hora de la misa se acerca, todas los rostros se vuelven hacia la sacristía por la que el Padre ha de salir, pareciendo caminar con dolor sobre sus pies perforados. Sentimos que la gracia misma se nos acerca, forzándonos a doblar las rodillas. El Padre Pío no es un sacerdote corriente, sino una criatura con dolor que renueva la Pasión de Cristo con la devoción y la radiación de quien está inspirado por Dios.

Tras llegar al altar y hacer la Señal de la Cruz, el rostro del Padre queda transfigurado, y parece como una criatura que se ha unido a su Creador. Las lágrimas caen por sus mejillas y de su boca salen palabras de oración, de súplica por el perdón, de amor hacia su Señor de quien parece convertirse en una perfecta réplica. Nadie de entre los presentes nota el paso del tiempo. Le lleva aproximadamente una hora y meda el decir la misa, pero la atención de todos está fijada en cada gesto, movimiento y expresión del celebrante.

Al sonido de la palabra «Credo», pronunciada con una convicción tan enorme, se produce una gran ola de emoción entre la muchedumbre. Y el más recalcitrante de los pecadores es llevado como por una corriente, que lo lleva al confesionario y a la renuncia a su vieja forma de vida[7].

Trabajador de milagros

El escritor Stuart Holroyd cuenta algunas de las muchas historias sobre la milagrosa intercesión del Padre Pío. Él escribe:

Durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, un general italiano, tras una serie de derrotas, se encontraba a punto de suicidarse cuando un monje entró en su tienda, y dijo: «Una acción así es una estupidez», y se marchó en seguida. El general no conoció la existencia del Padre Pío hasta algún tiempo después, pero cuando visitó el monasterio, lo identificó como el monje que en un momento crucial había aparecido, salvándole la vida.

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial un piloto italiano saltó de un avión en llamas. El paracaídas no se abrió pero el piloto milagrosamente cayó al suelo sin herirse, y regresó a su base con una extraña historia que contar. Mientras caía hacia el suelo, un fraile lo había tomado en sus brazos y lo había bajado suavemente a tierra. Su Oficial de Mando dijo que evidentemente el piloto estaba conmocionado, y lo envió a casa durante un tiempo.

Cuando le contó a su madre la historia de cómo había escapado, ella dijo: «Ese era el Padre Pío. Le recé tanto por ti». Entonces le enseñó una imagen del Padre. «¡Es él!», dijo el joven piloto.

Después fue a agradecerle al Padre Pío su intervención. «No ha sido la única vez que te he salvado», dijo el Padre Pío. «En Monastir, cuando tu avión fue alcanzado, lo hice planear hacia tierra a salvo». El piloto se quedó asombrado porque el acontecimiento al que se refería el Padre había ocurrido algún tiempo atrás, y no había ninguna manera normal en la que pudiera saberlo[8].

Su servicio hoy

En 1975, unos siete años después de su muerte, la maestra ascendida Clara Louise nos dijo que el Padre Pío es un maestro ascendido. El Padre Pío es fundamental con su ayuda a la Iglesia que los maestros han fundado en la era de Acuario. También es conocido por su capacidad de dar respuesta a las oraciones por curación. El Padre Pío fue reconocido oficialmente como santo de la Iglesia Católica el 16 de junio de 2002.

Notas

Mark L. Prophet y Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Los Maestros y sus Retiros, Volumen 2, “Padre Pío”.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, December 31, 1995.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, January 3, 1993.

- ↑ Kenneth L. Woodward, Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn’t, and Why (Haciendo santos: cómo determina la Iglesia Católica quién se convierte en santo, quién no lo hace y por qué), (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 157; C. Bernard Ruffin, Padre Pio: The True Story (Our Sunday Visitor, 1982), p. 361.

- ↑ Woodward, Making Saints, pp. 156–57.

- ↑ Michael Grosso, Who Is Padre Pio, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Woodward, Making Saints, págs. 156-57.

- ↑ Alberto D’Apolito, Padre Pio of Pietrelcina, pp. 253–56.

- ↑ Laura Chandler White, trad., Who is Padre Pio? (¿Quién es el Padre Pío?) (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1974), pág. 41.

- ↑ Ídem, págs. 39-40.

- ↑ Stuard Holroyd, Psychic Voyages (Viajes psíquicos) (London: Danbury Press, 1976), págs. 44–45.