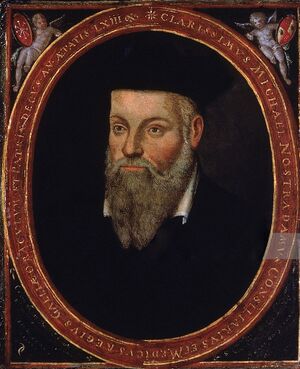

Nostradamus

Michel de Nostredame, born December 14, 1503,[1] at Saint-Rémy, in Provence, France, is commonly known by his Latinized name, Nostradamus. He has been called such things as “the man who saw tomorrow” or “the man who saw through time.” He is, without doubt, the most illustrious and mysterious of seers.

Early years

Nostradamus was the eldest of the five sons of Jacques and Reynière de Nostredame, a family of Jewish converts to Christ. At a young age he studied mathematics, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and the “celestial science” of astrology under his grandfather’s tutelage. At nineteen he studied medicine at Montpellier under the finest physicians. Taking time out to minister to those afflicted by the plague, Nostradamus completed his doctorate and went on to study under the philosopher Julius-César Scaliger.

Nostradamus practiced medicine throughout his life and became a renowned healer, dispensing unorthodox cures. Although he delivered many from the plague, he was unable to save his wife and children. After their tragic deaths he traveled, studied under the most learned minds of Europe, and became fascinated with alchemy, astrology and white magic.

He settled in Salon in 1547, married a widow of means and together they had six children. He converted the top floor of his home in Salon into a study and observatory, where he diligently wrote his prophecies in four-line verses called quatrains. He compiled these in groups of one hundred called Centuries, and they were first published in 1555.

As his prophecies proved more and more accurate, Nostradamus’ extraordinary fame traveled far and wide.

The source of his prophesies

In a preface to his prophecies, written to his infant son, Nostradamus claims that his visions reached to the year 3797. It is Nostradamus’ prophecies for our time that become the most fascinating—and frightening. Nostradamus has left us a vivid description of the challenges our generation may soon face.

Nostradamus said his predictions were divinely inspired and supported by astrological calculation. I believe that the spirit of prophecy that was upon Nostradamus came through the heart of Saint Germain. Nostradamus himself described the setting in which he received his prophecies.

Nostradamus is alone at night, seated in his secret study, which he tells us is a specially built room in his attic, when “a small flame comes out of the solitude and brings things to pass which should not be thought vain.”[2] Then, when all is set: “Divine splendor. The divine seats himself nearby.”[3] In this description, taken from the opening quatrains of Century I, the prophet suggests that he enters a meditative state and like an amanuensis records what “the divine” tells him.

Interpreting the prophecies

It is often argued that Nostradamus’ prophecies are so vague that they can be applied to virtually anything. “The style of the Centuries is so multiform and nebulous,” wrote historian Jean Gimon, summarizing this line of criticism, “that each may, with a little effort and good will, find in them what he seeks.”[4] That is not actually the case. Nostradamus intended his “enigmatic sentences,” as he explained to Henry II, to have “only one sense and meaning, and nothing ambiguous or amphibological [capable of having more than one interpretation] inserted.”[5]

Nostradamus’ prophecies, therefore, are obscure until overtaken by events. When the events occur, the quatrains become eminently clear and, because of his precise use of language, allow only one possible interpretation for each quatrain or series of related quatrains.

While Nostradamus described future events in concrete terms that limited his predictions to specific situations, the language he used added a mystical dimension to his prophecies. This mystical language helps convey his meaning and intent and reveals the depth and breadth of his own perceptions.

Nostradamus’ prophecies were obscure by design. The reasons for this are as complex as the quatrains themselves. He was writing at a time when one accused of witchcraft or black magic could be burned at the stake. Lee McCann, author of Nostradamus: The Man Who Saw Through Time, reminds us that “while Nostradamus was a boy preparing [to continue his education at] Avignon, five hundred of the piteous creatures accused of witchcraft were burned in Geneva.”[6]

Nostradamus did not want to be summarily executed by potential adversaries in Church or State. Nor did he want to interfere with God’s will by prematurely revealing the prophecies he was given. Nostradamus therefore set his prophecies down in a deliberately hard-to-understand mystical prose. In order to further disguise them he rewrote them into cryptic quatrains in chronologically organized Centuries.

The quatrains contain a bewildering mixture of French, Latin, Greek, Italian, Provençal, symbols, astrological configurations, anagrams, synecdoches, puns and other literary devices. Still he thought they were too easy. Nostradamus mentions a number of times that he is concerned about “the danger of the times” and “the calumny of evil men.” Just to be sure, he scrambled the order prior to their publication in 1555.[7]

Final years

In 1564, Nostradamus reached the summit of his career. While on a tour through France, the young King Charles IX and his mother, Queen Catherine de’ Medici, visited the prophet. The queen titled him Counselor and Physician in Ordinary. Not long after, in 1566, Nostradamus died in his study. He had left unfinished the seventh of his ten centuries and had barely begun an eleventh and a twelfth.

His epitaph read in part: “Here rests the bones of the illustrious Michel Nostradamus, alone of all mortals judged worthy to record with his almost divine pen, under the influence of the stars, the future events of the entire world.”

Sources

Elizabeth Clare Prophet with Patricia R. Spadaro and Murray L. Steinman, Saint Germain’s Prophecy for the New Millennium, ch. 2.

- ↑ Date based on the Julian calendar. December 23 by the Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ Jean-Charles de Fontbrune, Nostradamus 2: Into the Twenty-First Century, trans. Alexis Lykiard (London: Pan Books, 1986), p. 22.

- ↑ Edgar Leoni, Nostradamus and His Prophecies (New York: Bell Publishing Co., 1961), p. 133.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 103.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 329.

- ↑ Lee McCann, Nostradamus: The Man Who Saw through Time (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1941), p. 155.

- ↑ Leoni, Nostradamus, pp. 112, 327, 329.